Cultivating Conversations

★★★★★

In a world of fragmented relationships, conservative Anabaptists have the potential to be increasingly known for their gracious communication and hospitality. They will provide winsome, humble voices of clarity and discernment in a culture snowed under with the ambiguity and ungodly philosophies of social and broadcast media. Life-giving conversations will characterize their churches, schools and homes. Empathetic listeners and gracious counselors will outnumber the lonely and hurting. Iron will sharpen iron and truth will be spoken in love.

In a world of fragmented relationships, conservative Anabaptists have the potential to be increasingly known for their gracious communication and hospitality. They will provide winsome, humble voices of clarity and discernment in a culture snowed under with the ambiguity and ungodly philosophies of social and broadcast media. Life-giving conversations will characterize their churches, schools and homes. Empathetic listeners and gracious counselors will outnumber the lonely and hurting. Iron will sharpen iron and truth will be spoken in love.

This potential cannot be realized without communities of committed Christ-followers who have experienced the rich blessings of God and the clear leading of the Holy Spirit. Only within such communities can compelling, life-giving conversations be fostered. We desire and pray for this, and will also act. Presenting a gracious message that brings others to Jesus requires both speaking and listening skills. Developing these in our children and youth ought to be a focus in our communities.

This article will explore two foundational ideas behind the development of speaking and listening skills: the importance of practice and the deepening of thought processes that comes from practicing well. In addition, practical suggestions will be given for developing and cultivating speaking and listening skills in our homes and schools.

Successful Communication is Not Only for the Gifted

Speaking and listening skills are developed through practice. But perhaps we undermine this idea with some common expressions focusing on talent rather than practice. How often have you heard: “He’s such a gifted speaker?” Have you ever heard somebody ask: “How did he become such an articulate and effective speaker?”

We tend to approach conversations in similar ways. We assume that good conversationalists and discussion leaders have obtained some mysterious gifting enjoyed only by a privileged few. At a youthful and impressionable stage in my life, I remember hearing an outstanding conversation on a volatile topic. I can still picture the setting and participants. In this discussion, the proverbial elephants in the room were addressed and slain. The potential landmines were disarmed as issues were discussed and clarified. This gave space for opposing viewpoints to be heard. Why was this conversation working in places where others had failed? I remember noticing several things about those leading the discussion: their outstanding verbal abilities, their humility, and the clarity they brought to the topics at hand.

I was at first awestruck at the apparent scholarly thoughtfulness of the participants. They had seemingly attained a verbal adeptness inaccessible to the ordinary human. I longed to gain the mysterious skills they possessed. I wanted to contribute to similar discussions—ones that would allow us all to break through our clouded preconceptions and see the issues more clearly. I wanted the capacity to broach, listen to, and discuss difficult topics without causing rifts in relationships.

As I continued to listen to these discussions, I began to realize that what was happening was not rocket science. The most effective phrases and ideas consisted of simple one and two- syllable words. What was unusual was the humility and clarity that these words cultivated. “I think I hear you saying (summary of what was said). Did I hear you correctly?” “I’m not sure if I understood what you were saying about x. Could you talk more about that?” “I agree with what you said about x. What would you say about y?”

These discussion skills were, after all, attainable. These words could be practiced and learned. I could use these words and phrases to frame my questions and ideas. Even my young students could learn and practice foundational skills that would enable them someday to effectively use these kinds of language skills to cultivate wholesome interactions in the church.

We are no strangers to the need for practicing skills. Onlookers are consistently amazed at the cooking, homemaking and sewing skills of Mennonite women and the skilled labor of Mennonite men. It is not that we are genetically predisposed to these tasks. We have had thousands of hours of practice at these skills from an early age. The same type of diligence is necessary to cultivate good speaking and listening skills.

We ought to care about practicing speaking and listening skills in the same way that we care about practicing homemaking and craftsmanship. Learning to speak with clarity will sharpen the thinking of the day laborer as well as the practiced, seasoned speaker. But the sharpening is in the practice. Listeners and speakers not only gain clarity and grace through practice; they also have opportunity to strengthen and deepen their thought processes.

Deepening Thinking through Speaking and Listening

This is perhaps most evident when we interact with young children whose thought processes are developing rapidly. An experienced teacher advised me to expand thinking skills by using good questions to encourage and develop language skills. Prompting the child is a more effective way of building memory than simply supplying the vocabulary term that the child is struggling to retrieve. Giving the child a few words to begin a sentence is better than impatiently interrupting their stumbling words. Children gain deeper understandings of the topic under discussion as they practice putting words together in a coherent way.

As children talk about what they are learning, they not only benefit from practicing their speaking and listening skills, they also deepen and strengthen their thinking on that topic. An instructor at Faith Builders purposefully develops as a thinker by applying this strategy to the books he reads. After reading a book, he finds a willing audience and retells the main points of what he has read. Three retellings are enough to fix the new ideas and most powerful stories in his mind.

As children talk about what they are learning, they not only benefit from practicing their speaking and listening skills, they also deepen and strengthen their thinking on that topic. An instructor at Faith Builders purposefully develops as a thinker by applying this strategy to the books he reads. After reading a book, he finds a willing audience and retells the main points of what he has read. Three retellings are enough to fix the new ideas and most powerful stories in his mind.

As children retell stories to each other, they gain more than new information. As they hear other students talk, they see what they missed. As they hear themselves talk, they evaluate their own ideas in a more accurate way. Perhaps this is what Winnie-the-Pooh was thinking when he said, “When you are a Bear of Very Little Brain, and you Think of Things, you find sometimes that a Thing which seemed very Thingish inside you is quite different when it gets out into the open and has other people looking at it.”

Practice Begins at Home

We begin to practice speaking and listening skills at home. The way we speak to the babies and toddlers in our homes powerfully influences their language development and their lifelong learning potential. Children who are verbally adept tend to have parents who kept up a flow of conversation in the early days of their life. This conversation flows naturally through the course of the child’s

day, from diaper changes to shopping trips to the bedtime story. University of Kansas researchers Betty Hart and Todd R. Risley published a report on this phenomena called “The Early Catastrophe: The 30 Million Word Gap by Age 3.” Prior research showed that children of high-income families consistently outperform children of low-income families, with the gap being the widest between professional families and welfare families. This was not news to the educational community. What educators found puzzling was why they could not arrow the achievement gap by providing impoverished children with he same educational opportunities hat other children had. They also found that a stable and loving environment was not the core issue in the achievement gap. Even if they came from solid families, children from low income homes came to school with significant learning disadvantages.

The surprising result of this study was that by the age of 3, children from high income families had been exposed to thirty million more words than children from low income families. These findings highlight the key role of conversation in the homes. High income parents tend to converse more, use complex sentence structures, speak with precise vocabulary (vs. baby talk and slang), support children with positive words and affirmation, and read regularly to their children. What these parents offer their children can be offered regardless of income

The Questions We Ask

The kinds of questions parents ask heir children also develop their communication abilities. Professor Monisha Pasupathi, in her lecture series “How We Learn,” describes two common parental responses to a child’s storytelling.  When a child retells he story of an event during the day, some parents give little time for their child’s story. They focus on getting the facts and do not ask for their child’s perspective or feelings on the event. This approach is called the repetitive approach. Children who experience the repetitive approach learn limited communication skills.

When a child retells he story of an event during the day, some parents give little time for their child’s story. They focus on getting the facts and do not ask for their child’s perspective or feelings on the event. This approach is called the repetitive approach. Children who experience the repetitive approach learn limited communication skills.

Other parents patiently listen to their child’s stories while asking probing questions to encourage their child to give more details. In response to their parents’ support and interest, children tell more vivid, accurate and detailed stories. Parents who ask their children to elaborate on their stories in this way are using the elaborative approach. By school age, these children have acquired outstanding verbal skills that powerfully impact both their speaking and writing. Pasupathi speculates that these children not only have attained better verbal summarization skills, they also have gained reflection skills that help them to learn from their life experiences.

Pasaphuthi points out that storytelling skills, like other communication skills, are gained through time and practice. Stories are best told in the natural flow of shared work and play. I believe that conservative Anabaptist parents are uniquely positioned to help their children gain elaborative storytelling skills. Stay-at-home moms have more opportunities to strengthen their child’s storytelling because of the amount of time they spend together. Families sitting around the supper table provide an appreciative audience for children to practice their storytelling skills.

Speaking and Listening at School

As children reach the age of formal schooling, teachers sometimes assume that their students will gain the necessary speaking and listening skills as they do their daily assignments. But teachers ought to be thinking constantly about how to craft class discussions, ask questions, and teach students to communicate. After all, school  is where, for the first time, children hear divergent ideas, decide when to insert their thoughts, and practice expressing their opinions clearly and compellingly to a group of peers.

is where, for the first time, children hear divergent ideas, decide when to insert their thoughts, and practice expressing their opinions clearly and compellingly to a group of peers.

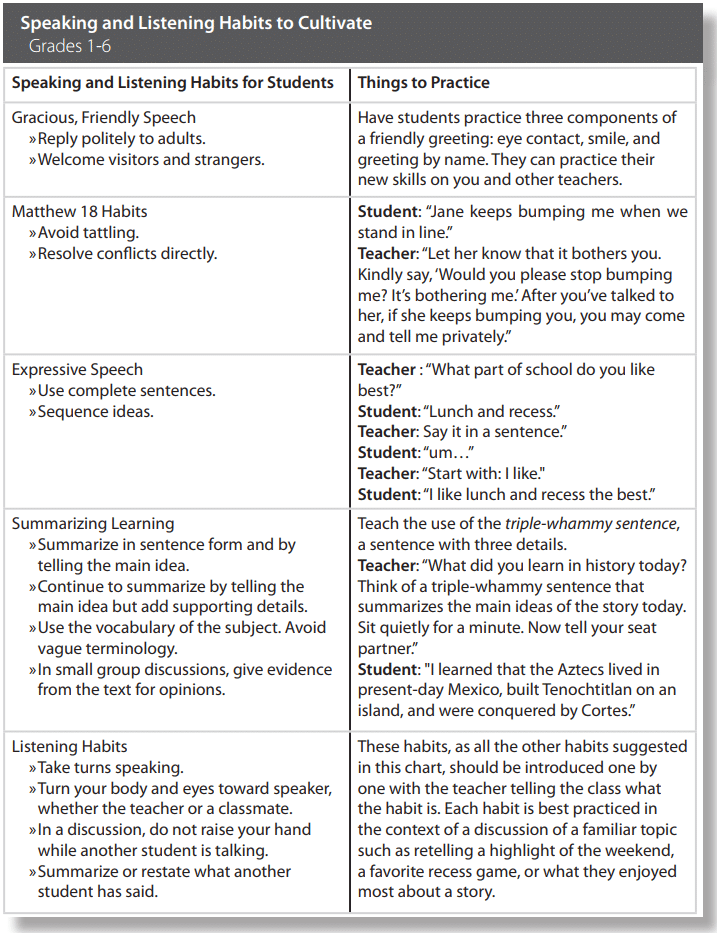

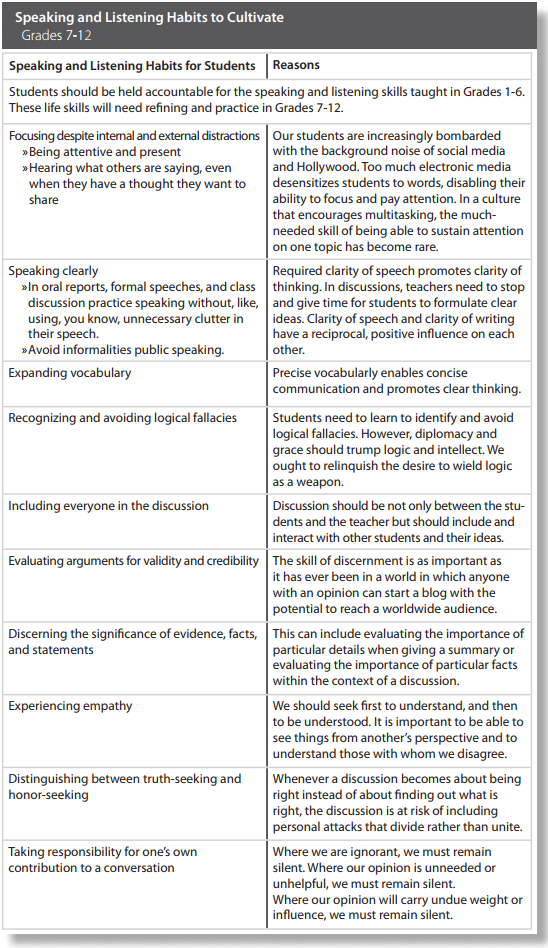

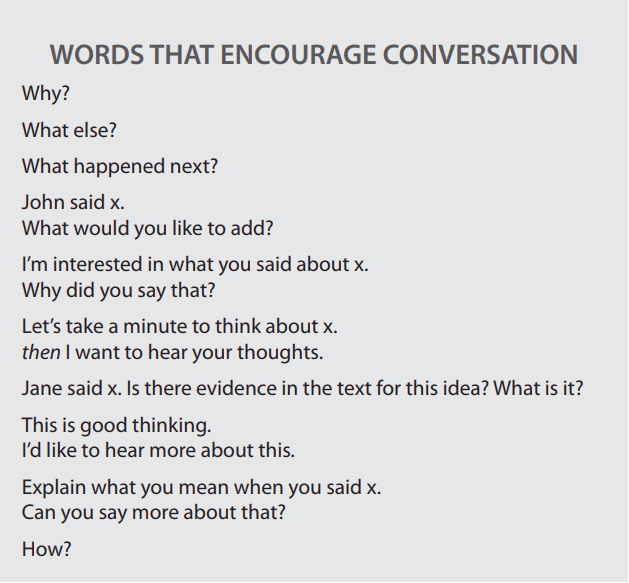

The preceding charts outline areas in which schools could assess and strengthen teaching practices. Many of these techniques could also be used in the home. Students who practice these skills are on the path to contributing to their churches and communities with effective and gracious communication skills.

Our Anabaptist communities offer havens of peace and wholesomeness in the clamor of 24-hour news cycles, social media, and driven lifestyles. Our traditional family values and practices portray a vision of belongingness to those jaded by the broken realities around them. As followers of Jesus we possess a compelling message to share with others. May we prepare the next generation to communicate effectively with grace, humility and clarity.

Works Cited

Keene, Ellen Olliver. Talk About Understanding: Rethinking Classroom Talk to Enhance Comprehension. Portsmouth, New Hampshire: Heinemann, 2015.

Hart, Betty and Todd R. Risley. The Early Catastrophe: The 30 Million Word Gap by Age 3.

Pasaputhi, Monisha. How We Learn. Chantilly, Virginia. The Teaching Company, 2015. Video.This article originally appeared in a Faith Builders newsletter. Download more free resources at FBEP.org.

Related Items

Leave a Reply

Feedback