Cultivating Healthy Class Discussions

★★★★★

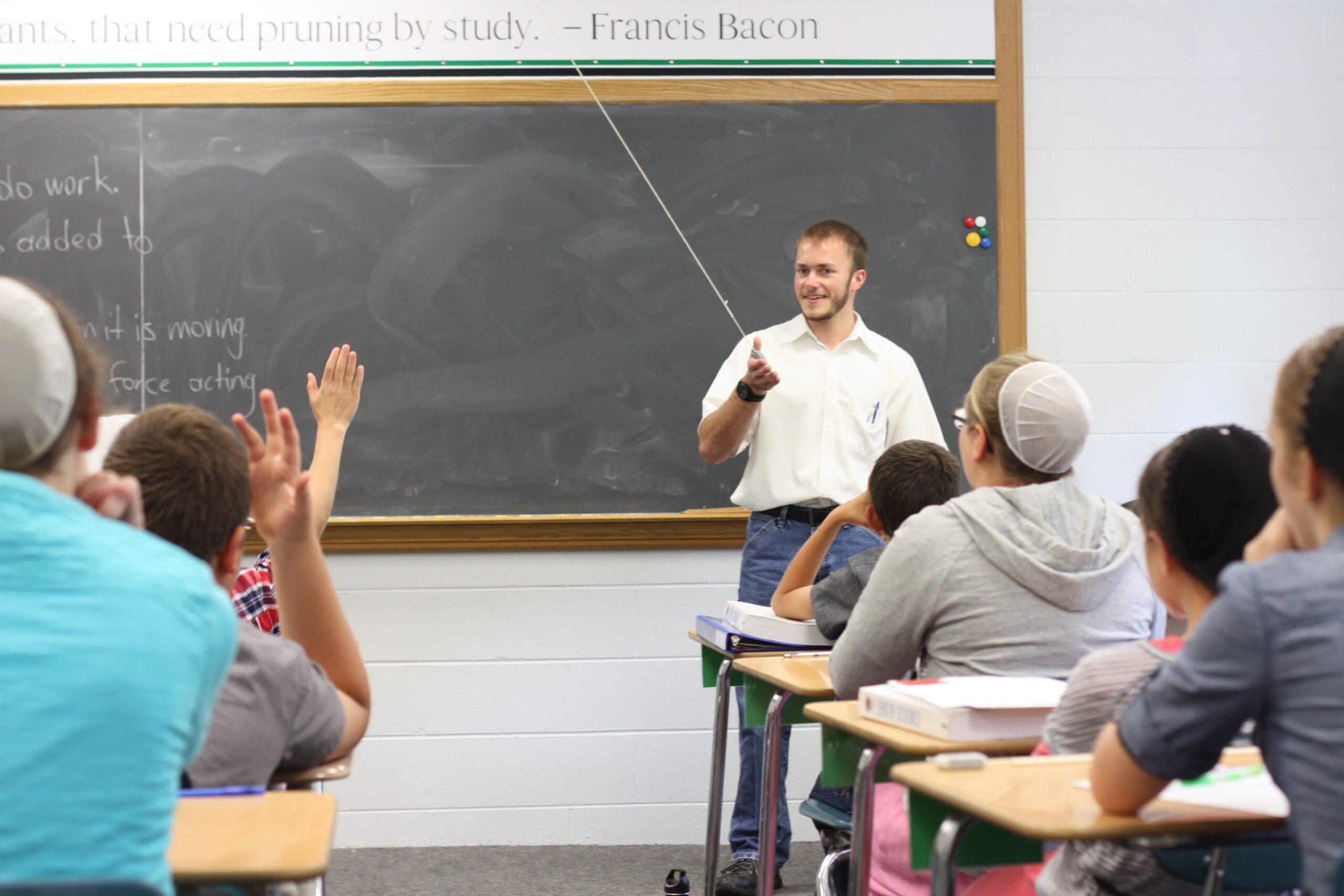

Stimulating, productive discussions are among the most rewarding classroom experiences for both teachers and students. But making them happen can be challenging. I’m not sure which is worse: the excruciating silence of unresponsive students, or the crescendo of chaos that builds as a class spins out of control. Here are some strategies that I’ve found helpful for promoting focused, energized class discussions in grades seven through twelve.

Establish procedures

I want my class periods to consist of conversations more than lectures, where students ask questions and contribute their thoughts freely and naturally. With this goal in mind, I do not think it is always necessary or even helpful for students to raise their hands and wait for me to call them before speaking. While hand-raising is encouraged, my general rule is that students may speak appropriately without raising their hands as long as they maintain order and follow my instructions. To help keep order, I have established a few simple rules and procedures for class discussion, which I teach students at the beginning of each year. Note that these rules and procedures work well for me, but they won’t necessarily work for every teacher and every group of students. Consider the personalities present in your classroom and find rules and procedures that will promote healthy discussion in your situation.

First, I expect students’ contributions during class to be relevant rather than distracting. Students who persist in distracting talk face consequences, such as being required to talk at length on the subject with which they distracted the class, except at lunch when they’d rather do something else. Second, I expect students to respect each other, speaking in turn and listening to each other. Third, I give signals to show students when I specifically do or do not want them to raise their hands and wait to be called on before speaking. When I ask for a response and suspect that a cacophony of voices is likely to rise, I raise my hand while I ask my question to signal that students must raise their hands this time. When I ask for a response and suspect that hand-raising would restrict the flow of conversation, I put my hand to my ear to signal that students should just call out their responses. Finally, I reserve the right to require hand-raising whenever things start to get disorderly. If a student speaks out of turn after I’ve announced this restriction, I immediately interrupt him and cheerfully remind him to raise his hand.

Plan opportunities for response

Ideal rules and procedures don’t do much for healthy discussion if the teacher never gives students a chance to say anything. This needs to be more than a perfunctory “Any questions?” at convenient intervals. Plan questions of your own that help guide students toward meeting your objectives for the class period. Here are general types of questions that are useful in many situations:

“What connections do you see between _____ and _____?”

“What do you think about_____?”

“How would you feel if _____?”

“How would you respond to _____?”

“Can you explain _____?”

“What would cause ______?”

“What would be the consequences of _____?”

Not all responses need to be verbal. A quick raise-of-hands poll:“Raise your hand if you think _____. Now raise your hand if you think _____ instead” can get all students thinking and responding without saying a word, and often leads to productive comments from students who wish to explain their responses.

There are two pitfalls I try to avoid when seeking student responses. First, I try to limit questions that call for brief, factual answers. While these can be a good way to review material quickly or to add some call-and-response rhythm to a class, they are too often awkward attempts to disguise lectures as discussions. Second, I watch out for bottomless pits of stray thoughts and wild guesses. When they get in a certain mood, students will take up whatever’s left of a class period spouting off every odd hypothesis that my questions make them think. When I sense that it’s one of those days, I specify that students should answer a question only if they truly believe that their responses are realistic possibilities.

Reward engagement, not just correct responses

As long as it is sincere and relevant, every student response is a good response. Even when a student answers a question incorrectly or gives a comment that reflects faulty understanding, he deserves to be recognized and encouraged for making an effort to engage with the material and connecting it with his prior knowledge to the best of his ability. For example, students often say that the Old Testament was written in Greek, or that the New Testament was written in Hebrew. These are understandable mistakes that demonstrate some knowledge of the subject at hand. I often respond to this kind of mistake by saying, “That is incorrect, but I can understand why you would think that,” “Not quite; you’re probably thinking of something else that is closely related,” or “That is the correct answer to a different question.” I emphasize that school is for learning, and that we often learn by making and correcting mistakes.

Reward productive curiosity

It is vital to acknowledge every sincere question that students ask, and to discuss as many as possible. Yes, some questions are mischievous, irrelevant, or too far beyond the scope of the class period, but I try to make room even for these. If a student wonders whether animals have souls, or wants my opinion on Ford versus Chevy, my standard response is that I’d be happy to talk all about it during lunch. I really mean this, and occasionally students do join me for mealtime conversations arising from such questions. I do my best to address every serious question in class. This may even include “Do animals have souls?” depending on the spirit in which it is asked.

A person is never more open to learning something than at the time he asks about it. We teachers would be foolish not to take hold of such opportunities. Sometimes it’s worth it to chuck a whole lesson plan in favor of a student’s question, and sometimes time permits us only to acknowledge the question and try to get back to it in the next day or two. Addressing every question shows students that we respect them and honor their desire for knowledge and understanding.

What have you found to be helpful in cultivating healthy class discussions? Share your thoughts and experiences in the comments, or in the forums.

Leave a Reply