Grading with Rubrics in the English Classroom

When English teachers get together, the topic of grading will come up—often with complaints about the time grading takes and the difficulty of grading essays fairly. While part of that is just the nature of the job, essay grading can be made simpler with the effective use of a well-written rubric.

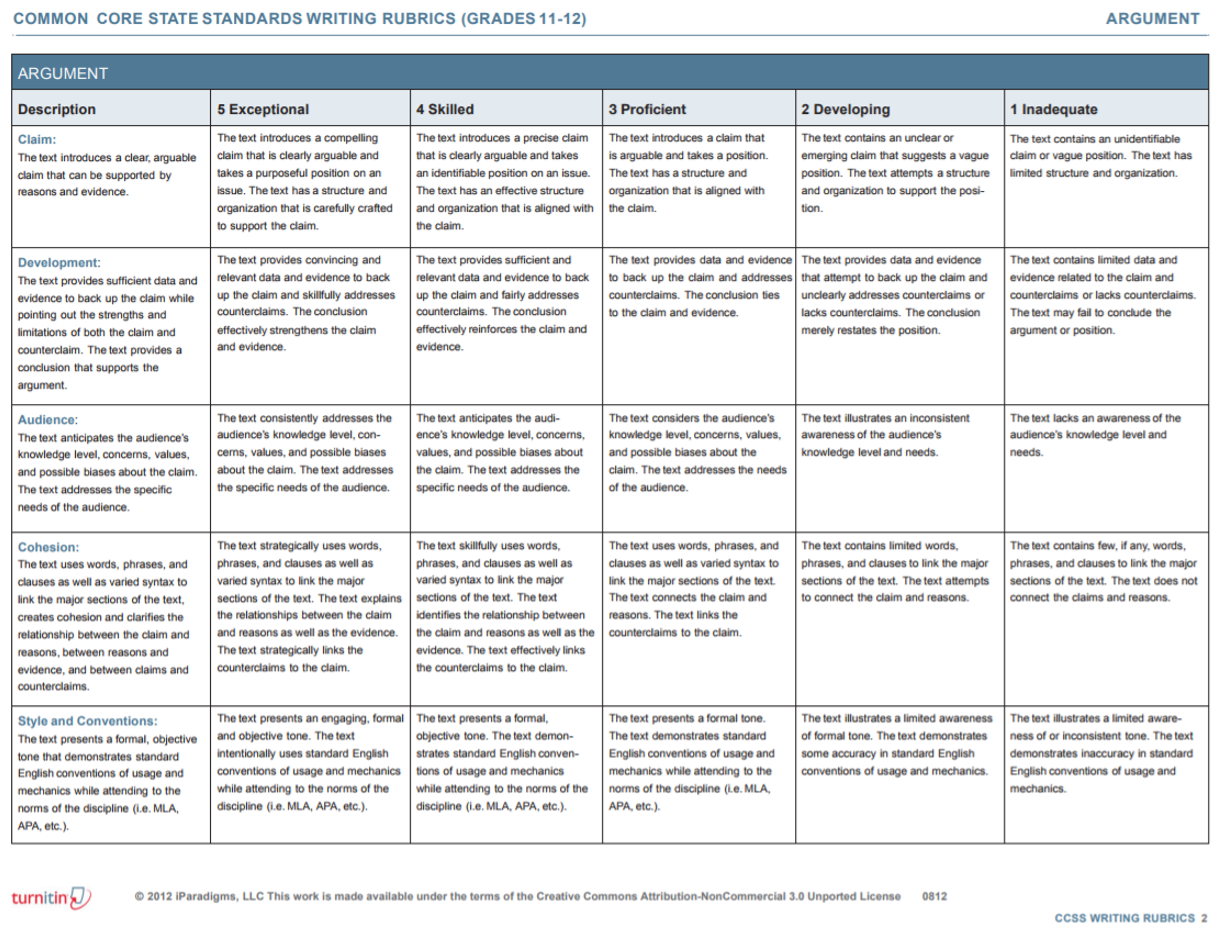

A rubric is a list of characteristics desired in a final assignment, with different points assigned for each level of achievement. An analytical rubric displays in a grid-like formation that matches a description of student achievement to different levels, such as exceptional, good, satisfactory, and poor, or to different numbers of points, such as 5, 4, 3, 2, 1 (see below).

(Note that while this rubric comes from the sometimes-debated Common Core, it provides a good starting place and can be adapted, as described later in this blog post.)

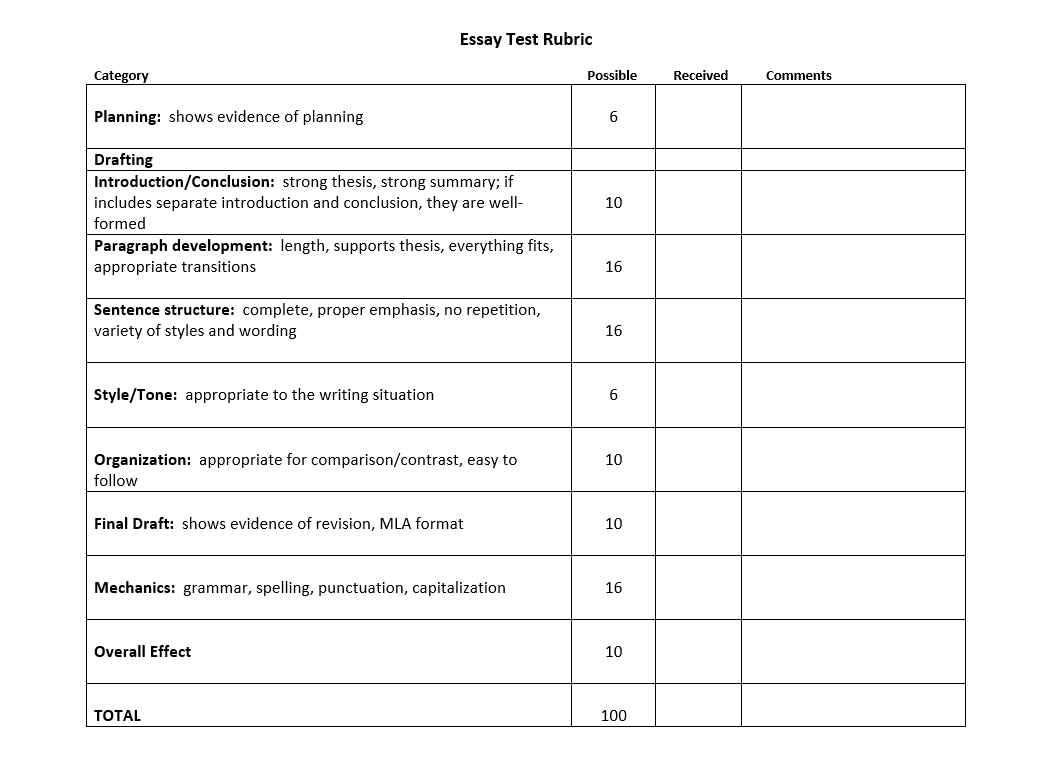

A holistic rubric describes the desired outcome for each characteristic, and the grader attaches a point amount to the characteristic (Fuglei 1).

While some critics argue that rubrics stifle the student’s creativity and limit helpful feedback, most English teachers agree that rubrics allow the most objective grading for essays. Used as a teaching tool during the writing process, the rubric allows the writer to see the needed characteristics before turning a paper in. The teacher can explain each attribute on the rubric as a writing lesson. Then used as an assessment tool, the grader can look specifically for the required specifications when checking the final draft. The key, then, is to create a fair and easily used rubric that still provides feedback for the student. Here are some tips.

- Don’t start from scratch when creating a rubric. Most writing curricula include grading rubrics. If not, they can be purchased or even found for free online or in teaching resource books.

- Modify already existing rubrics to meet your student’s needs. If there is a specific writing characteristic that you are emphasizing, be sure it is included on the rubric. Or if you know your class needs help in a certain area, include it as a goal on the rubric.

- Individually tailor rubrics to students. By leaving points for one category open, each student can set an individual goal (or the teacher can set it) to work on for a specific assignment. I often build upon a previous rubric, using a student’s lowest category to set the individual goal on the next rubric.

- Leave room on the rubric for comments. Rather than just assigning points, tell the student why that amount of points was assigned. While comments can also be written on the paper itself, it often helps to have them all together on one page.

- Keep rubrics as a portfolio of writing progress throughout the year. The student can use each rubric as a guideline for the next paper. At the end of the school year, the cumulative rubrics show the progress made.

- Keep a rubric to a one-page length. Longer rubrics are cumbersome both for the writer and the grader. A shorter rubric provides focus.

- Make the point value for each category equivalent to the importance of the category. If the teacher is focusing on mechanics, that should be a larger proportion of the total points. Or if the main goal is organization, that should be the largest category. I always do my rubrics out of 100 points to make it easy for students to see their grades.

- Use wording that matches the wording in the assignment. For example, if the teacher describes mechanics as “grammar, spelling, and punctuation,” that is how it should be worded on the rubric.

- Use the rubric throughout the writing process. Go over the rubrics with students at the beginning of the writing assignment. As each lesson is completed, remind students of what part of the rubric they are working on. During the revision and proofreading process, have students work through the rubric one category at a time.

Works Cited

“Common Core State Standards Writing Rubric.” 2014. https://www.csun.edu/sites/default/files

/Common%20Core%20Rubrics_Gr11-12_turn_it_in_0.pdf. Accessed 10 Feb. 2024.

Fuglei, Monica. “Rubric’s Cue: What’s the Best Way To Grade Essays?” Resilient Educator, 12

Nov. 2014. https://resilienteducator.com/classroom-resources/essay-grading-

rubrics/#:~:text=Because%20a%20rubric%20identifies%20pertinent,criteria%20in%20the%20 writing%20assignment. Accessed 10 Feb. 2024.

Photo by Afif Ramdhasuma on Unsplash.

Related Items

Leave a Reply

Feedback