Technology Detox

★★★★

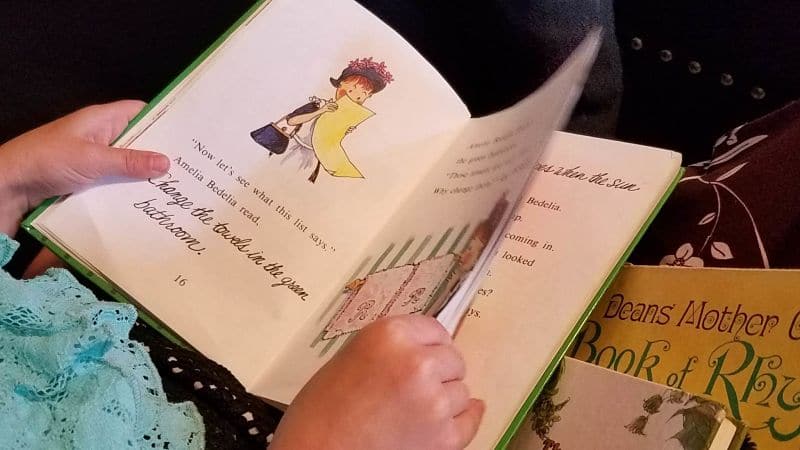

Stock image from Unsplash

Stock image from Unsplash

As a foster parent, I regularly come into contact with children who have been raised with technology as their wet nurse. They may have been born on a screen, for all I know—certainly under the sight and sound of one. When they were tired, or bored, or hungry, or restless, or wakeful, or alone, they found comfort and excitement in the constant novelty of a flickering television or PlayStation.

They could say PS4 before they knew who Jesus was, and discuss the intricacies of Fortnite and Call of Duty before their moral formation knew what to say about it.

I will not propose for a moment that technology toxicity is to blame for who they are, and who they became, for the gaps in their minds and hearts. By the time they land in my home, most of them have had enough trauma, isolation, unmet needs, and heartbreak to work measureless damage on its own. But I will add that technology didn’t help.

Toxicity is not a word I use lightly. Current science shows that early screen time in frequent doses damages a child’s development. In baby and toddlerhood, his eyes and heart and brain crave human interaction and responsive connection. Sedentary screen time at this age is detrimental, across the board.

Are you enjoying my categorical statements? Here’s another:

The content my children have seen should not be enjoyed by any human, much less a preschooler. When I look up the titles they cite, I have no words. Who thought unleashing this on innocents was anything less than criminal?

They are hollow-eyed and restless, unable to focus on anything for long. What are books? Books are boring. Their hands are soft little flabbypads, noticeably weaker and less coordinated than those of children half their age—unable to open a jar of peanut butter or press an eraser effectively to a page, much less perform the intricate muscle movements required to write their name, use a scissors, or build a craft. I am not making this up. I’ve watched it.

What do they do, little urban citizens of virtual worlds, when they arrive in a home where the only screen time for preschoolers is an hour video with the family on Saturday night? How do they live?

Here are some of the strategies we use for detoxing.

1. We communicate.

Children raised on excessive technology have not learned the most basic rules for talking and listening to other humans. To answer a question. To respond physically when their name is spoken (turning a head, calling a reply). To stop rattling after a while, and let another speak. Especially, to look into the eyes.

We are big talkers and listeners in this family; it’s our best strength.

So without thinking about it, we step closer when they call. We get down on our knees and we look into their eyes and we listen. We say each other’s names dozens of times a day. We sit in a circle and eat our dinner facing each other, and we chat. We request verbal responses to verbal instructions. When we are not sure what a child is telling us, we stop and wait and ask questions and put on our detective hats and sometimes call in another family member for help, until the Ah-ha! moment breaks. The child looks into our eyes and smiles a little, startled by the satisfaction of difficult communication resolved. You heard me.

Within days, we see a change in a child’s ability to communicate meaningfully. Eye contact improves. Automatic responses pop out. Enunciation sloppiness cleans up because someone is listening, and it matters that he understands me.

2. We listen to the monologues, then change the subject.

We don’t forbid discussions of video games, and what level my cousin was on, and the superninja demigod who just about got us at the intersection blah blah blah. We listen peacefully while we drive to a family visit or church or the grocery store, and then we say, “Oh look! A robin!”

We don’t force engagement in the here and now—the real. We just make it as tantalizing as we can.

3. We invite engagement with books.

Again, we do not require involvement. But books are always lying around our house. At any moment, someone is usually sprawled on the couch, lost in the pages. Dad or Mom sits down for story time, and invites each kiddo to bring two books.

For techie children, it usually takes a few days. Maybe weeks. Books don’t move and flicker and change and glow. But we’ve never met a child yet who didn’t come around—who didn’t find that + + + + + equals quiet peace and great pleasure.

Then one day, they are too silent, and we go flying to check on them, and find—miracle of miracles—they are lost in a book of their own.

4. We wear clothing free of advertisements and digital characters, with few exceptions.

Don’t underestimate it. We quietly tuck away the Hulk shirts and Loot Llama hoodies and Spiderman shoes. We choose the stripes and the polka dots and the pretty colors. We are no longer identifying ourselves with that set, and certainly not performing free advertising for them.

My husband made this choice early in parenting, for our own family’s sake, and we do not regret it.

5. We play and play and play and play and play and play and play and play. Outside.

“I made a snow angel once,” my newly-arrived foster child says, in his soft squeaky voice, “and I almost froze to my death from cold.” The woods are scary, because “that time when I lived in the trailer there were mean kids hiding there, and we ran away and got scratched by the thorns.”

Perceptions can change.

When shared with siblings who know the magic (how to light a fire and build a fort and push the swing and bounce us really high and pull the wagon), the outdoors is a place of endless delight, discovery, and imagination. Not so much alone. Because while you would think that living in fantasy worlds enables imagination, it actually kills it. All the imagining was done for my foster children. They didn’t have to ask questions. They didn’t have to invent or create or fill in the details. They were splashed and bombarded and choked by endless stimulation.

The school questions that drive my son to tears are not, “What is four plus six?” but, “If you had a clean-up machine like The Cat in the Hat, what could it do?” Or “What do you think will happen next in our story?” How am I supposed to know?

Play is education. And nature is incredibly therapeutic. It’s dynamic and wholesome and earthy and huge and robust. There are chickens in it, and darling new kittens. There are pinecones to turn into people, and daffodils to pick for Mom. (Sorry they came out of the flowerbeds, but LOOK AT THESE FLOWERS RIGHT HERE IN MY OWN HAND!) My children come inside rosy-cheeked and filthy, full of stories.6. We have fun as a family – as real live people.

We invite our new kiddos into the joy of family togetherness.

- Going out for ice cream.

- Cooking supper on sticks in the backyard.

- Planting the garden.

- Baking cookies with Mom.

- Cleaning the house, three M&M’s per job completed.

- Taking a long walk to the park.

- Sharing “Family Time” just before bed, sitting around the couches singing and talking about our day.

- Best of all, what my kids call “Wrestling/Tickling Matches” on the living room floor with Daddy. Nothing else brings so much joy, and our foster kids, who hang on the fringes and watch and declare they don’t like being tickled… and then edge in a little closer… are soon shrieking and tackling with the rest. (I personally will have none of it. But my husband is a boss.)

Maybe this doesn’t feel like detoxing from technology. But the joy of the one doesn’t compare to the other. There are people! Who like me! And we get up and do stuff!

7. We provide tactile toys.

Building and manipulating objects happens with the hands, not the controller. We offer a big bin of Lego, and a huge car blanket with roads and houses, and Matchbox cars to drive on it. We keep a large stash of crayons, and child-friendly scissors. We love Play-Doh. It strengthens the hands and pleases the fingers and engages the mind. We do a lot of giant floor puzzles. Magnetic tiles to build into cars and structures. Bubbles to blow. Sidewalk chalk for writing it big. Watercolor paints. Mr. Potato Head pieces to assemble. A toy kitchen with lots of pots and pans.

8. We remain what we are, and the majority wins.

The lovely thing about adding one or even two people to a home is that they can add their glorious personhood and diversity and interest and flavor and uniqueness and joy to our family, without us being overcome by it. We add it in. And gently, we dismiss what we cannot permit. But our family, our core unit of constancy and change, remains the same. New children are the raindrops. We are the river, always receptive but not easily diverted into fresh streambeds.

If our new big brother isn’t into Xbox games, and we never play them anymore, our interest kind of peters out. Maybe it revives when we meet birth grandma at the visit; we may talk as animatedly as ever about the fifth level and our dangerous escapes, but with the Zooks we begin to merge into new paths.

Kids adapt. They are not as resilient as we’ve always been told, but I’ll hand it to them – they are highly adaptable. Detoxing can happen. Harmful effects can be mitigated.

And guess what? Our big brother has a really cool whistle made out of an acorn cap.

Sources and Further Reading

- Screen-Free Parenting – Have You Spoiled Your Child Today? Meet S.P.O.I.L.

- BBC – No Sedentary Screen Time for Babies

- American Academy of Pediatrics – Children and Media Tips

- Kids Health – Screen Time Guidelines for Babies and Toddlers

Related Items

Leave a Reply

Feedback