Using Maps and Genealogies to Understand the Bible’s Story Line

★★★★☆

I still remember reciting the seven continents with my fellow small-bodied second graders, remember the exact rhythm and tone of our voices rising in unison: “Asia. Africa. North America. South America. Antarctica. Europe. Australia!” My teacher sometimes had us do map drills, where we’d stand in front of the big wall map—fascinating for all its strange shapes and strange words—and race to see who could find a continent first.

My fourth grade teacher had her students memorize the states and capitals and held a capital bee to see who had them mastered. My fifth grade teacher used flashcards to help us memorize the shapes of the different states. These sorts of activities helped me to become geographically literate and, at a basic level, to understand the structure of the world I live in.

However—though I remember one teacher explaining to us the path of Paul’s missionary journeys over a series of devotionals—none of my teachers laid out the structure of Bible names and places and enforced their memorization. It took a college class in my adult years to bring me to that point of familiarity. In a class called The Fundamental Texts of Christianity, our professor taught us that the storyline of the Bible comes alive when you have pegs to hang things on. In this class, we not only reviewed the missionary journeys of Paul, we learned to sketch from memory a rough map of the world he lived in and the prominent cities he journeyed to.

So now when I’m reading through Acts, I have a picture in my mind of exactly where Iconium is (in Galatia, not far from Lystra and Derbe) and when Paul stopped there (on all three of his missionary journeys). I know that Philippi was home to many retired Roman soldiers known for their patriotism; that Corinth was a wealthy trading center located just on the other side of the isthmus from Athens; and that Paul wrote his letter to the Romans from Corinth during his third missionary journey. Knowing these things makes Paul’s journeys and his epistles real to me in a way they never have been before.

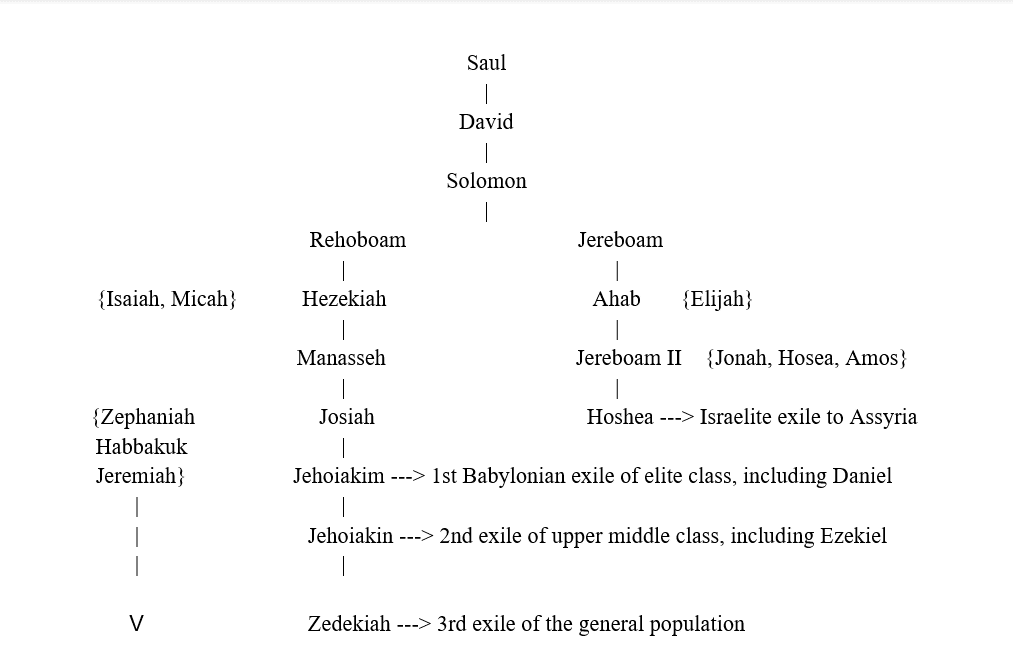

Our professor also had us learn to sketch from memory the wilderness journey of the children of Israel and a simplified map of Palestine during Jesus’ time. In addition, we learned some of the basic genealogies of the Bible: the line of godly men from Adam to Jacob, the prominent Israelite kings and the prophets who prophesied during their reigns; and the line of Persian kings, Jewish leaders, and Jewish prophets involved in the Judean return from exile.

As an example, the simplified line of Israelite kings we learned looks like this:

Although not every king and prophet are included (such a complex list would frustrate students), having this simplified list of kings and prophets has already helped me in understanding the overarching storyline of the Bible. When I opened my Bible to Hosea this morning, I was able to quickly identify who he was prophesying to (both Israel and Judah) and what he foresaw for each nation (the destruction of Israel and continued mercy for Judah). Because I also knew the Assyrian conquest of Israel happened not long afterward, Hosea’s prophecy made perfect sense.

Genealogies and maps in Bible class—just as in history or geography—can enable your students to gain a big picture understanding of the structure of the Story.

Leave a Reply